What follows is the text of my talk at the 2017 MLA Annual Convention, slightly modified for the web. I spoke on a panel that showcased new forms of nineteenth-century digital scholarship. (Also featured were Mark Algee-Hewitt and Annie Swafford). An essay-length version of the talk is in the works, but since I’m heads-down on my book manuscript at the moment, I’m posting my remarks here.

NB: If you’d like to read some of the more design-oriented work I’ve done on the subject, please see my paper from the 2016 IEEE VIS conference, co-authored with Catherine D’Ignazio, that outlines our principles of feminist data visualization and specifies some design questions for engaging them.

This talk departs from a seemingly simple question: “What is the story we tell about the origins of modern data visualization?” And as a set of follow-ups, “What alternate histories might emerge, what new visual forms might we imagine, and what new arguments might we make, if we told that story differently?”

To begin to answer these questions, I’ll focus on the work of one visualization designer from the nineteenth century, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, whose images are rarely considered in the standard story we tell about the emergence of modern visualization techniques. When they are mentioned at all, they are typically described as strange—and sometimes even as failures. You can see one of them just below.

To us today, accustomed to the charts and graphs of Microsoft Excel, or the interactive graphics that we find on The New York Times (dot com) on any given day, we perceive schemas like this as opaque and illegible. They do none of the things that we think that visualization should do: be clear and intuitive, yield immediate insight, or facilitate making sense of the underlying data. But further questions remain: why have we become conditioned to think that visualization should do these things, and only these things? How has this perspective come to be embedded in our visual culture? And most importantly for us here today, what would it mean if we could view images like these, from the archive of data visualization, instead as pathways to alternate futures? What additional visual schemas could we envision, and what additional stories could we tell, if we did?

So I’m going to inhabit my method, and frame my talk today in terms of an alternate history. First, I’ll walk you through the visual schema that you see above-left, proposed by Peabody in 1856. Then I’ll talk about some of the more speculative work I’ve done in attempting to reimagine her schema in both digital and physical form. And then I’ll try to explain what I’m after by describing this work, as you saw in the title of this talk, as feminist—

More specifically, I’ll show how Peabody’s visual method replaces the hierarchical mode of knowledge transmission that standard visualization techniques rest upon with a more horizontal mode, one that locates the source of knowledge in the interplay between viewer, image, and text. I’ll demonstrate how this horizontal mode of knowledge transmission encourages interpretations that are multiple, rather than singular, and how it places affective and embodied ways of knowing on an equal plane with more seemingly “objective” measures. And finally, I’ll suggest that this method, when reimagined for the present, raises the stakes for a series of enduring questions—about the issue of labor (and its relation to knowledge work), the nature of embodiment (and how it might be better attached to digital methods), and the role of interpretation (and how is not only bound to perception, but also design).

But I think that’s enough of a preamble. So, to begin.

Elizabeth Palmer Peabody was born in Massachusetts in 1804. Today, she is most famous for her proximity to more well-known writers of the American Renaissance, such as Emerson and Hawthorne. (Hawthorne was actually married to her sister, Sophia). But Peabody had impact in her own right: the bookstore that she ran out of her home, in Boston, functioned as the de facto salon for the transcendentalist movement. She edited and published the first version of Thoreau’s essay on civil disobedience, which appeared in her Aesthetic Papers, in 1849. And interestingly, she’s also is credited with starting the first kindergarten in the United States.

But in the 1850s, Peabody set off to ride the rails. She traveled as far north as Rochester, NY; as far west as Louisville, KY; and as far south as Richmond, VA, in order to promote the US history textbook she’d recently published: A Chronological History of the United States. Along with boxes of books, Peabody traveled with a fabric roll the size of a living room rug, which contained floor-sized versions of charts like the one in the image above, which I’ll tell you only now is a visualization of the significant events of the seventeenth century, as they relate to the United States. (This image that you see is a plate from the textbook, measuring, at most, 3 inches square).

In her version of a sales pitch, Peabody would visit classrooms of potential textbook adopters, unroll one of her “mural charts” (as she called them) on the floor, and invite the students to sit around it to contemplate the colors and patterns they perceived.

Peabody’s design was derived from a system developed in Poland in the 1820s, which employed a grid, overlaid with shapes and colors, to visually represent events in time. At left you see, on the bottom left of the page, a numbered grid, with each year in a century marked out in its own box. On the top right you see how each box is subdivided. So, top left corner for wars, battles, and sieges; top middle for conquests and unions; top right for losses and divisions, and so on. And shapes that take up the entire box indicate an event of such magnitude or complexity that the other events in that year didn’t matter.

Peabody’s design was derived from a system developed in Poland in the 1820s, which employed a grid, overlaid with shapes and colors, to visually represent events in time. At left you see, on the bottom left of the page, a numbered grid, with each year in a century marked out in its own box. On the top right you see how each box is subdivided. So, top left corner for wars, battles, and sieges; top middle for conquests and unions; top right for losses and divisions, and so on. And shapes that take up the entire box indicate an event of such magnitude or complexity that the other events in that year didn’t matter.

The basic exercise was to read the narrative account in Peabody’s textbook, and then convert the list of events that followed, like the one you see below-left, into graphical form. And I should note, at this point, that the events are color-coded, indicating the various countries involved in a particular event.

So now I’ll return to the original chart (at left), and you can see now, hopefully, that England is red, the Americas are orange, and the Dutch are teal—those are the colors that dominate the image. The French get in on the act, too, in blue. And if you cross-reference the chart to the table of events, you can see, for instance, the founding of Jamestown in 1607; and the settlement of Plymouth in 1620—that’s the red on the right—and, interestingly, the little teal box stands for the first enslaved Africans arriving in Virginia at that same time.

So now I’ll return to the original chart (at left), and you can see now, hopefully, that England is red, the Americas are orange, and the Dutch are teal—those are the colors that dominate the image. The French get in on the act, too, in blue. And if you cross-reference the chart to the table of events, you can see, for instance, the founding of Jamestown in 1607; and the settlement of Plymouth in 1620—that’s the red on the right—and, interestingly, the little teal box stands for the first enslaved Africans arriving in Virginia at that same time.

But I think it’s safe to say that no one in this room could have known this without me explaining how to interpret the chart. And for researchers and designers today, who champion the clarifying capacity of visualization; or for those who believe that datavis is best deployed to amplify existing thought processes—for such people, Peabody’s design would be a complete and utter failure. For Peabody, though, this near-total abstraction was precisely the point. Her charts were intended to appeal to the senses directly, to provide what she called “outlines to the eye.” Her hope was that, by providing only the mental outline of history, and by insisting that each student interpret the outline of history for herself, she would conjure her own historical narrative, and in that way, produce historical knowledge for herself.

So this is where the feminist aspects of Peabody’s approach to data visualization begin to emerge. Anticipating some of the foundational claims of feminist theory, Peabody’s schema it insists upon a multiplicity of meanings, and locates knowledge in the interplay between viewer, image, and text. Hers is a belief in visualization, not as clarifying or illuminating in its own right, not as evidence or proof of results, but as a tool in the process of knowledge production.

At this point, it also bears mention that for Peabody, the creation of knowledge took place through a second mode: through the act of creating the images themselves. Peabody also printed workbooks, with sheets like the one you can see at left, and she envisioned the exercise, ideally, as one not merely of cross-referencing events to their visual representation, but of constructing the images they would then study. So you can see one student’s attempt below-left. And below on the right is another, by someone who appears to have given up all together. (These images come from a blog post by the Beinecke, but I’ve traveled to several archives across the northeast U.S. and seen the same thing). I used to show these images to get a laugh, but I know now, because at this point I’ve tried it a number of times, that this method is a very hard thing to actually do.

At this point, it also bears mention that for Peabody, the creation of knowledge took place through a second mode: through the act of creating the images themselves. Peabody also printed workbooks, with sheets like the one you can see at left, and she envisioned the exercise, ideally, as one not merely of cross-referencing events to their visual representation, but of constructing the images they would then study. So you can see one student’s attempt below-left. And below on the right is another, by someone who appears to have given up all together. (These images come from a blog post by the Beinecke, but I’ve traveled to several archives across the northeast U.S. and seen the same thing). I used to show these images to get a laugh, but I know now, because at this point I’ve tried it a number of times, that this method is a very hard thing to actually do.

But that seems to be both a liability of the form, and also the point. Peabody devised her method at a moment of great national crisis—the decade leading up to the Civil War—and she recognized that the nation’s problems would be difficult to solve. Her goal was to prompt an array of possible solutions—one coming from the creator of each chart. And her hope was that, by designing new narratives of the past, her students would also imagine alternate futures.

In fact it was this aspect of Peabody’s system—the idea that, by insisting that each student participate in the creation of each chart, they would also each create their own interpretations of them, that seeded my desire to reimagine these charts for the web.

I’d already recognized, in Peabody’s method of first scanning a list of events, then identifying the type of each event and the nations involved, and then plotting it on the chart, a method that was strikingly procedural. And the process of cross-referencing between text and image seemed to me, even more, like the form of interaction you see all over the web. But it was her insistence on the need to create the charts in order to create knowledge that confirmed my decision to pursue the project. What would we discover, about the past, or about the present, if we were to make Peabody’s scheme accessible to students and scholars today?

This was the point that I enlisted a graduate student in Human-Computer Interaction (HCI), Caroline Foster, who helped design the really beautiful site that you’ll see in a minute. And I was also fortunate to be able to work with two very talented computer science undergrads, Adam Hayward and Shivani Negi, who helped with the technical implementation. And together, we set about creating this site. (NB: Erica Pramer, who graduated last year, helped with an earlier version of the project).

Below you can see some screen-shots from the four interactive modes: “Explore” (top left), which shows you how the events and their visual representations align; “Learn” (top right), which guides you through Peabody’s original lesson; “Play” (bottom left), which gives you a blank grid to color in; and “Compare” (bottom right), which generates a timeline on the basis of the current dataset, and displays it alongside the data as it’s stored in CSV form, as it’s listed in the text, and as it’s displayed on Peabody’s grid. (There are also some narrative components of the site, and while we’re still fixing bugs and tweaking the text, we encourage you to explore the site and send us your feedback).

There’s a lot more to be said about the eerily object-oriented way in which Peabody structures her data, and I touch on that in one of the interactive elements of the site, but in terms of my current argument, the salient point is how the clarity and legibility of the timeline, by contrast to Peabody’s grid, shows just how conditioned we’ve become to certain ideas about what visualization should and should not do. To us today, accustomed to a standard typology of visual forms, we can form a really quick rank order of these images. The timeline is better, we say, because it yields immediate insight. Who the heck knows what is going on with that grid?!

But what if we understood the purpose of visualization differently? What if we were supposed to stop and think hard about what we were seeing, and what it meant?

For my part, I’ve been thinking about Peabody’s charts in their most striking instantiation—those mural charts on the floor—and how they demand a different mode of sensory engagement altogether. They replace the decorative and utilitarian function of a rug with an experience designed to generate knowledge, and in so doing, they require viewers to reconsider the actual position of their bodies in relation to their objects of knowledge.

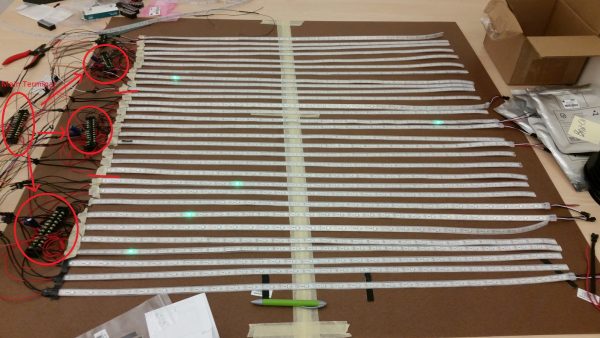

This feature has prompted me to undertake a second project to implement a floor-size version of Peabody’s charts, which you can see at lest in some very early phases. (You can read about our current progress on the DH Lab blog). So in the top image, you see a matrix composed of 900 individually addressable LEDs, and in the bottom, you see the touch interface that we’re developing, which makes use of conductive tape and neoprene in an almost matrix-like keyboard interaction, so that you’ll be able to toggle each square off and on. And as my students and I carefully measure each strip of tape, and solder each part of each circuit together, I think back to Peabody’s own process of fabrication.

This feature has prompted me to undertake a second project to implement a floor-size version of Peabody’s charts, which you can see at lest in some very early phases. (You can read about our current progress on the DH Lab blog). So in the top image, you see a matrix composed of 900 individually addressable LEDs, and in the bottom, you see the touch interface that we’re developing, which makes use of conductive tape and neoprene in an almost matrix-like keyboard interaction, so that you’ll be able to toggle each square off and on. And as my students and I carefully measure each strip of tape, and solder each part of each circuit together, I think back to Peabody’s own process of fabrication.

When I mentioned that she made floor-sized versions of the charts as a sort of marketing ploy, what I didn’t mention was that, as an additional incentive, she promised a handmade chart to any classroom that purchased the book. Writing to a friend in 1850, Peabody revealed that she was “aching from the fatigue” of making the charts for each school. She described how she would stencil shapes and colors onto a large piece of fabric, and how a single one took her 15 hours. As you can see from the text of the letter, she yearned for her book to become profitable so that she could hire someone to “do this drudgery for [her].”

It speaks both to poor book sales, and to the perceived lack of value of the charts, that none have been preserved. But what we do have, in letters like these, is evidence of the actual physical labor, as well as of the knowledge work, involved in producing these charts. And more specifically, with her references to the fabric and to the drudgery, it’s labor in feminized form.

Let me take some time unpack this, because it’s this observation that I want to end with, as I return to the question of alternate histories, and their impact on how we produce knowledge.

A lot of people—or, well, the handful who have ever thought to comment on Peabody’s work—observe that Peabody’s charts look like Mondrian paintings. And it’s true that, in their abstraction, they evoke the modernist grid. But thinking about the feminized labor of making the charts brings to mind a second point of reference, which is quilting.

What you see here (above) are two quilts from the area of Alabama known as Gee’s Bend. These quilts, created by a close-knit community of African American women in years that span the twentieth century, have in fact recently been posited as offering an alternate genealogy of modernism. This genealogy derives from folk art and vernacular culture, and centers this community of women who would otherwise be placed far to the side in the story of modernist art.

You might already be starting to guess where I am going with this line of thought—Peabody in relation to standard accounts of data visualization; the women of Gee’s Bend in relation to Mondrian. And it’s true—women’s work of all kinds, be it education or quilting, has long been excised from the dominant accounts of their fields.

But there’s another aspect of this comparison that I want to draw out—which is how both the quilts of Gee’s Bend, and charts of Elizabeth Peabody, offer alternative systems of knowledge-making. Both employ shape and color to visually represent events in the world. And both, also, rely upon sense perception—and more specifically, the tactile experiences of the body—in order to assimilate those shapes and colors into knowledge. In her textbook, Peabody even talks about things like pleasure, and she emphatically rejected the idea of a single interpretation of history in favor of an exchange between the subject and object of knowledge. For Peabody, the abstraction of the grid was preferable to a more mimetic form because it “left scope for a little narration.” In other words, she believed that if her visualizations provided the contours of history, the viewer could then—both literally and figuratively—color them in.

And therein lies her principal lesson: about what information constitutes knowledge, about how that knowledge is perceived, and about who is authorized to produce it. That, to me, is why this project—the historical part and the technical one—is a feminist one. Because it brings renewed attention to the role of interpretation, and to the modes of knowing outside of what we’d typically consider to be visualizable, such as intuition, or affect, or embodiment.

As humanists, we’ve been trained to recognize the value of these alternate forms of knowledge, just as we’ve been trained to register the people, like Peabody, who stand on the periphery of the archive. These are often people whose stories we would otherwise lack sufficient evidence to be able to bring to light, whether it’s evidence in the form of data, or just the archival record.

And this is where I see a convergence in the historical and theoretical work surrounding the archive, and the more technical, but equally theoretical work relating to data and its visual display. It’s where I think humanists have real lessons to teach those who design visualizations—and as I begin to speak more with designers and researchers outside of the humanities, I’m increasingly convinced of this fact. But it’s also a space where I think we, as digital humanists, could make an intervention in our own scholarly fields. It’s not only by taking digital methods and applying them to humanistic questions; or even what I’ve demonstrated here today: how humanistic theories allow us to better understand certain digital techniques. Rather, what I’d like to see as we “renew the networks” of nineteenth-century digital studies, to borrow a phrase that Alison employed to introduce this session, is to insist on a richer intersection of the digital with the humanities, as both critical and creative, theoretical and applied, both the contours and the coloring in. That’s what I envision as the shape of things to come.

Thank you.